Exploring the Enigmatic ‘Cosquer Cave’: Paleolithic Mysteries Underwater in France

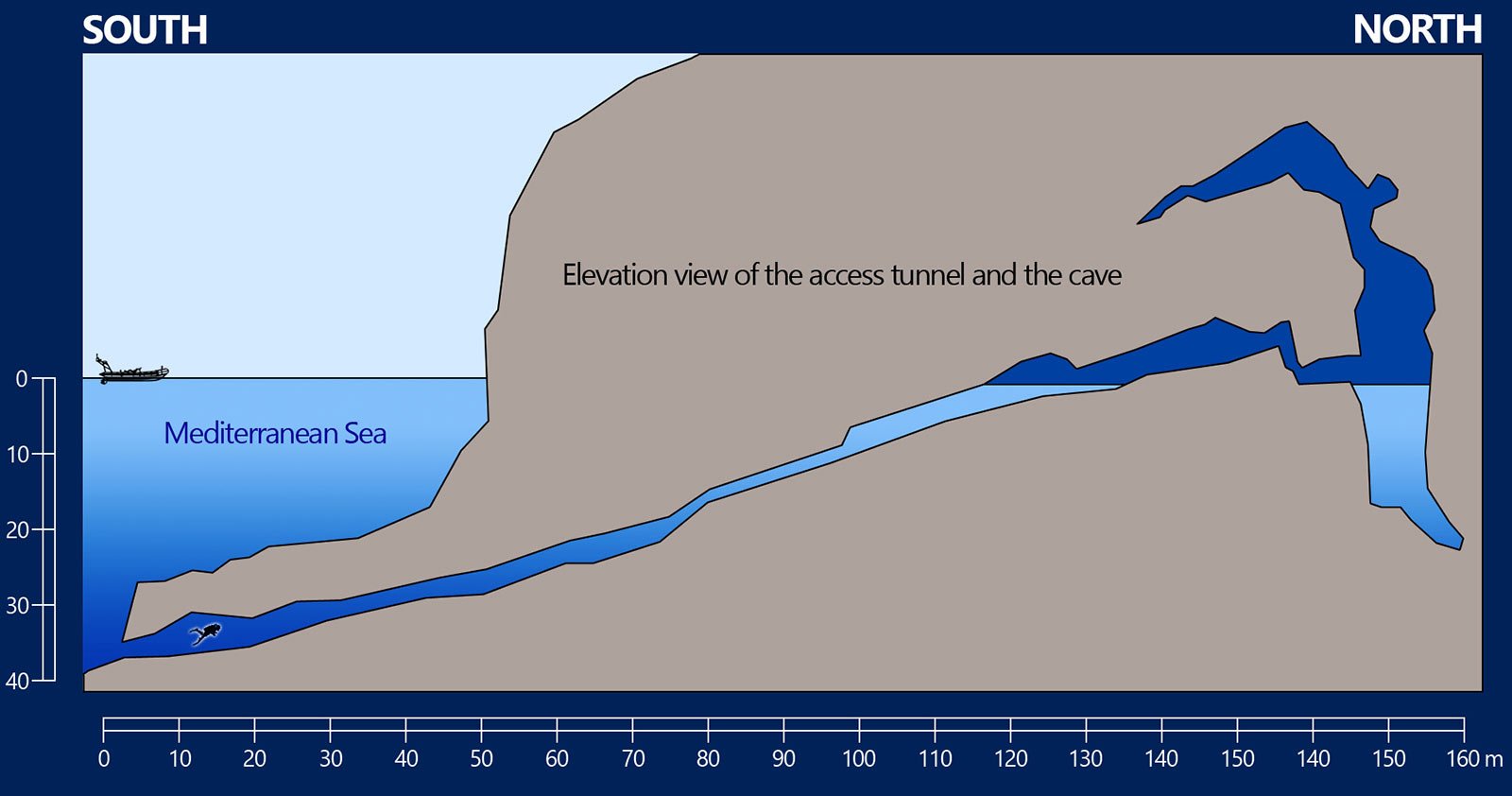

The Cosquer Cave is located in the Calanque de Morgiou in Marseille, France, near Cap Morgiou. The entrance to the cave is located 37 m (121 ft) underwater, due to the Holocene sea level rise. The cave can now be accessed by divers through a 175 m (574 ft) long tunnel; the entrance is located 37 m (121 ft) below sea level, which has risen since the cave was inhabited. During the glacial periods of the Pleistocene, the shore of the Mediterranean was several kilometers to the south and the sea level up to 100 m (330 ft) below the entrance of the cave.

It was regularly visited for several thousand years, over a period ranging from 27,000 to 14,000 BC. However, it was first authenticated by an expert on the Neolithic called Jean Courtin, as it proved impossible to find an archaeologist specialising in the Palaeolithic capable of diving to a depth of 37 metres and swimming along a dark, relatively narrow passageway.

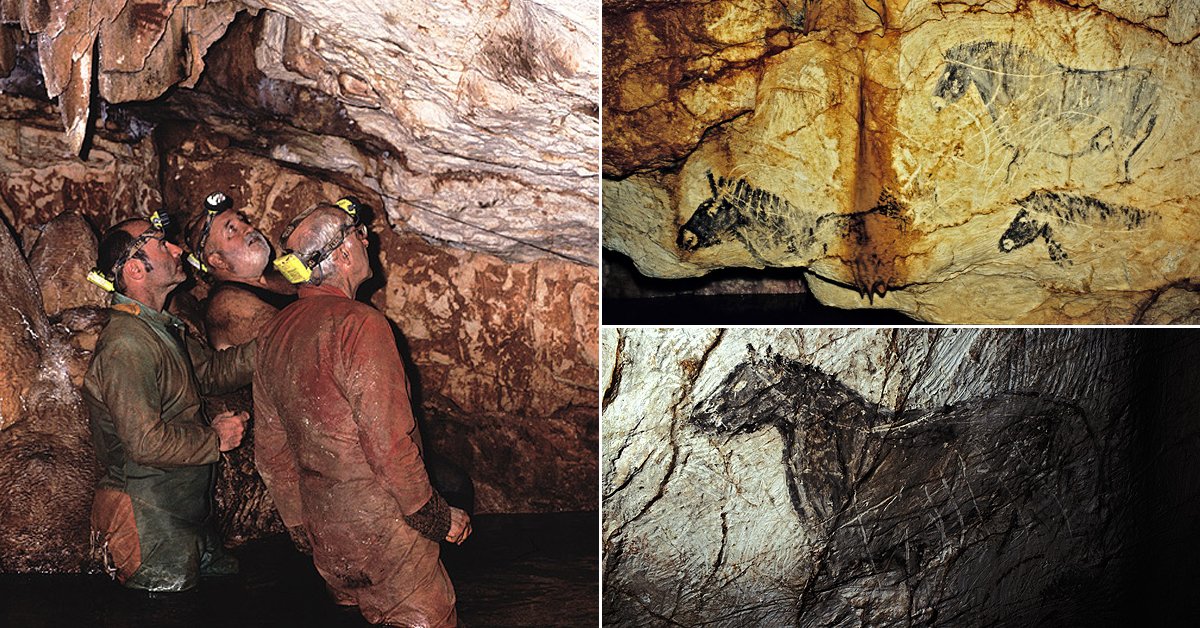

The cave contains various prehistoric rock art engravings. Its submarine entrance was discovered in 1985 by Henri Cosquer, a professional diver. The underwater passage leading to the cave was progressively explored till 1990 by cave divers without the divers being aware of the archaeological character of the cave. It is only in the last period (1990-1991) of the progressive underwater explorations that the cave divers emerged in the non-submerged part of the cave.

The prehistoric paintings were not immediately discovered by the divers to first emerge from the other side of the sump. The cave was named after Henri Cosquer, when its existence was made public in 1991, after that three divers became lost in the cave and died.

Prehistoric artists drew and painted animals but never humans, apart from their hands. From this point of view, the Cosquer cave is no exception.

Four fifths of the cave, including any cave wall art, were permanently or periodically submerged and destroyed by sea water. 150 instances of cave art remain, including several dozen paintings and carvings dating back to the Upper Paleolithic, corresponding to two different phases of occupation of the cave:

Older art consisting of 65 hand stencils and other related motifs, dating to 27,000 years BP (the Gravettian Era).

Newer art of signs and 177 animals dating to 19,000 years BP (the Solutrean Era), representing both “classical” animals such as bison, ibex, and horses, but also marine animals such as auks and a man with a seal’s head.

In the cave, marine animals make up a significant proportion of the figures. Auks, seals, fish and various markings that may represent jellyfish were painted or engraved on the walls. An auk can also be seen on the “ceiling”. This is probably a great auk, which was still widespread in the North Atlantic in the nineteenth century.

Cosquer isn’t the only site that features hand stencils. In fact, this appears to be a pattern that is specific to the Gravettian culture in Europe. The hands may have been mutilated or injured, but the most plausible hypothesis is that they represented a kind of code, a language of communication between hunter-gatherers, like that used not so long ago by the indigenous peoples of North America. But the meaning of these signs or codes is no longer accessible to us today.

The men, women and children whose handprints have been found in the cave were Homo sapiens sapiens, in other words, they were identical to modern humans in every way. It should be borne in mind that people in the prehistory never lived deep inside caves but rather near the cave mouth, under shelter, or in the open air.